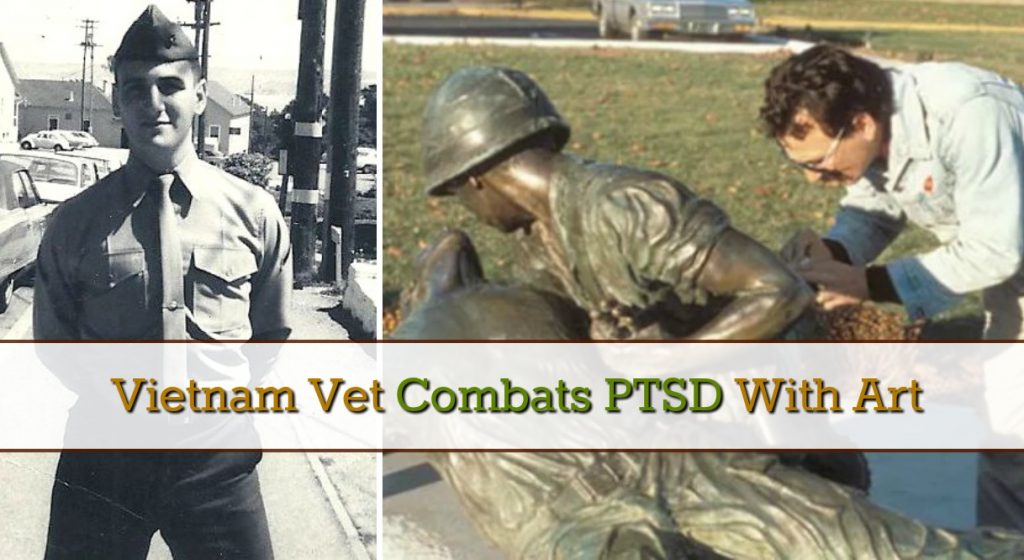

The year was 1969. The Vietnam War had been underway for 14 years when 18-year-old Steve “Pi” Piscitelli joined the Marines. The New Jersey teen appreciated the legacy of military service demonstrated by his father, a WWII vet who had served in the Navy, and Steve knew that he wanted to do his part as well.

Steve recalls, “My siblings asked dad who the toughest soldiers were, and without taking a breath, my dad said, ‘The Marines.’ He said it so matter-of-factly that it just stuck with me. I then thought, ‘I’ll be a Marine then.’”

The “street-corner tough” teen began his military training as a 0311 “Grunt” Rifleman, and studied Vietnamese at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, CA. Steve earned the rank of corporal with Fox Company, Second Battalion, Fifth Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, Second Platoon.

At just 19 years of age, Steve arrived in Vietnam and would soon be forever changed. He was placed in dangerous situations and learned a great deal about who he was and what he was capable of. “I fired a 106 recoilless rifle (like a cannon), and also rockets, flamethrowers, and explosives. As part of the anti-tank assault, we’d put explosives in a sack, run up to a tank, and throw it,” Steve recalls.

It Was a Free-For-All

The scrappy New Jersey teen always carried a knife and had been quietly observed by a man named “Gorilla.” Steve recalls, “One day he approached me about going on our own missions. There’s no term for this other than ‘Killing Teams’ and it’s not in the written history.”

Steve shares that although the war history was written by officers, most of the small-unit actions were done by privates and sergeants. “There were only two of us and we had no radio; nothing but a t-shirt, a pistol, a grenade and a knife. We would go out and find the enemy by smell (from cigarettes or cooking food), and as I got close, I could hear them speaking Vietnamese. We would fire and run back to the perimeter. I did these missions enough times that I still feel it at night…the disdain.”

Wounds and Purple Hearts

Steve served in the military for a total of one year, ten months and a handful of days, yet it was enough time to be wounded three times and to earn two Purple Hearts. Steve recalls, “I was only over there for nine months, and was injured in hand-to-hand combat and I didn’t know I was wounded. When they called in for casualties, I didn’t realize until later that I had been burned and was bleeding.”

Steve blamed his unawareness on more than adrenaline. He explains, “It’s crossing over into combat-induced psychosis or going berserk. I’ll just say that after that, my own men were very leery of me and happy that I was on their side.”

Steve’s other major injury came from the detonation of a landmine. He was hit with shrapnel in the knee, hand, neck, eye, thigh, ankle, and calf. “The opening on my back was only an inch and half, but because of the pressure, I started losing organs out of my back.”

Homecoming and the Negative U.S. Reception

Steve returned home, but like many other Vietnam vets received an inhospitable welcome. The 19-year-old returned with a broken body — he had shrapnel bits inside him, had to learn to walk all over again, and experienced severe knee and back pain. “The climate towards Vietnam was incredibly negative and I couldn’t hide the fact that I just came back. I walked with a limp, used a cane, and had the haircut.”

By night, Steve couldn’t sleep because of nightmares. By day, he was harassed and rejected by his fellow Americans. Steve describes, “When I was walking with my cane, people in passing cars would shout, ‘Murderer,’ ‘Baby killer’ — things like that. I was fired from my first job once they found out I was a Vietnam Vet. I couldn’t get hired.”

Fortunately, Steve had a supportive family who took him in and drove him to medical appointments. He shares, “I lucked out by having a large, loving family. A lot of vets didn’t have that and so they did drugs, ended up in jail, or committed suicide.”

Making His Way Through Art

Like other veterans, Steve came home with invisible wounds, and the country was caught off-guard. “The term PTSD didn’t even exist back then,” he shares. “Many of our men came home and could not reintegrate into society. Disabled American Veterans (DAV) started checking it out. In my case, because it was so clear — wounds, grenades, mines, hand-to-hand, point blank — ‘War Neurosis’ is what they labeled it. It was such a terrible name, it doesn’t mean much; you can’t look at the name and say ‘Oh I know what that means.’”

At the VA hospital, Steve immersed himself in fine art. Steve was self-taught and shares, “I started looking at the great masters like Da Vinci and Michelangelo and copied their work and developed a skill. My art therapist said ‘Don’t copy,’ so I got mad, sculpted and drew a whole bunch of things — all war art. When they came in the following Monday, the entire staff was stunned. They sat me down and said, ‘You’re not going to be a chef anymore, you’re going to be an artist.’”

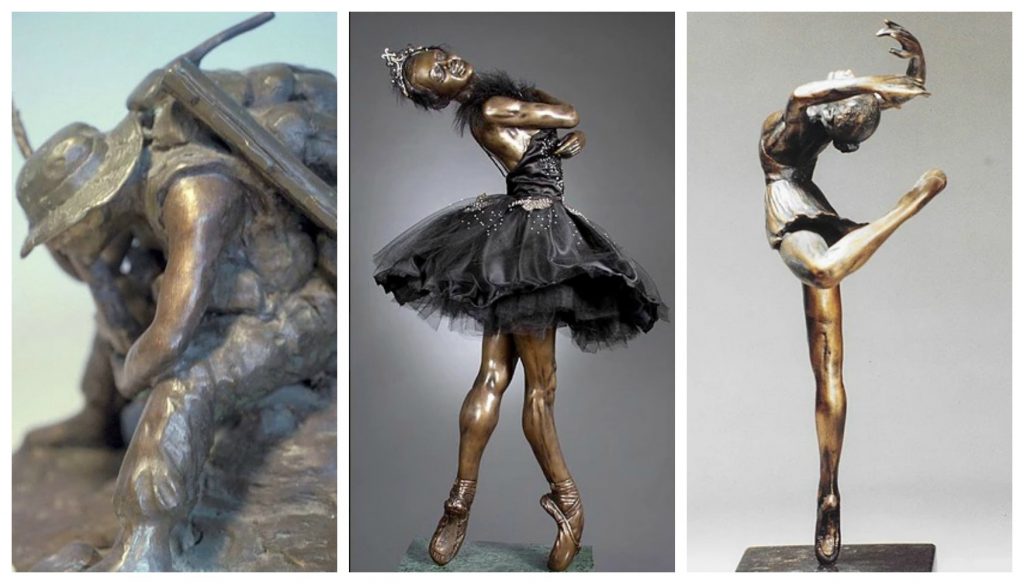

The VA encouraged Steve to attend U Mass for a degree in Fine Art. Steve fell in love with sculpture and found great pleasure in creating. He took war material — bronze — and melted it down to turn it into beautiful works of art. “I enjoy taking anything that can be used as a weapon and turning it into the opposite. I turn the ugly into beautiful, and dance is the most beautiful human endeavor. So now, instead of glorifying male violence, I nearly deify female beauty.”

Throughout Steve’s blossoming art career, he sought assistance and treatment to heal from his Vietnam experience. He explains, “In 1980, the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM – III) described what we now call PTSD. There were about 15 symptoms and I had almost all of them. I was diagnosed by the county mental health clinic, so when I went to the VA hospital, they could no longer ignore it.”

Steve attributes his healing and success to his ability to talk about the experience. “There are men who can’t talk about it. They get frustrated and angry and they don’t know how to articulate. Living with warriors all my life, I was able to talk about it. No one wanted to hear it, but when I didn’t talk about it, I’d develop ulcers from stress.”

Steve also feels a tremendous amount of appreciation for DAV. He shares, “In 1978, DAV set up storefront drop-in centers for Vietnam vets, because they knew there was a big problem. DAV has legal power and can represent the warriors to the VA. DAV did the most amazing things for veterans and much of that was taken over by the VA. I still use mine twice a month, I see the therapist and it’s great because a lot of things are happening in the world right now. It releases the pressure of the memories and the trigger points that set me back into combat.”

PTSD — You Aren’t Alone

For others struggling with PTSD, Steve advises, “Get to a vet center immediately, even if there is no problem because it gets you into the system. To go to the VA is daunting, annoying, it’s bureaucratic, and there is a backlog. The vet center gets you in right away with a one-page DD-214 and they set you up to see someone. It’s still a drop-in center and I would suggest that you go and start talking. Do not hold it in, and if you’ve got a problem, get help because no one else is going to help you.”

Steve also advises staying away from self-medication through drugs and alcohol. “I lost more people to drugs and alcohol than I lost in combat. Get to the vet center and start working on the rest of your life.”

From Warrior to Sculptor

Steve is now in his 60s, retired, and enjoys creating art, spending time with his wife Kathi, and their five cats. He regularly visits the vet center and looks forward to biannual reunions with Vietnam battle buddies and other veterans.

Steve still suffers from chronic back pain and — just five years ago — his doctor removed some shrapnel from his shoulder. This “souvenir” had been with Steve for more than 40 years.

Steve appreciates the shift in attitude towards service members and shares, “If you ask a Vietnam vet, they will tell you that we weren’t appreciated. ‘Anything for our boys in uniform’… that was gone. But now, after 9/11, whenever I show my ID at the airport, I get thanked for my service.”

Whereas Steve was once in the position to destroy, now he can’t help but create, again and again.

Steve has created more than 500 pieces and has transitioned from war themes to dancers and female portraits. All of his pieces are inspired by life experiences, war memories, or live models. Steve has created war monuments in Bristol Township, PA and Tallahassee, FL. He created a bust of Frank Zappa for the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, FL, and his large ballerina bronze stands outside the Orlando Ballet in Orlando, FL. Steve’s work has been heralded and shown in galleries and museums throughout the Central Florida region.

Steve closes with, “I dealt with war imagery by making statues of what was bothering me. In order to counterbalance that depressing, miserable subject, I took the most beautiful form of human endeavor—which is dance—and began making dancers just simply as a balance.”

Learn more about Steve Pi and view his art at stevepiart.com.

We thank Steve for sharing his remarkable story with us, and for his selfless service.

Comments

Powered by Facebook Comments

I love your art! Thank you for your service! You are an inspiration!

I am so excited to see this here Steve is an incredible artist and teacher. When I was younger I had an opertunity to learn from him during a period of my life where I had experienced a lot of trauma and his stories and experiences as well as his creative expertise and knowledge he shared has never left me. He has an increasible message on how much creating can heal and on how art can show others what words alone can not always convey.